![]()

Martian water ice has been known about for more than 200 years because Martian polar ice caps are visible from Earth in telescopes. Since the Space Age began in the 1960s, images collected by spacecraft at Mars have shown geological features that suggest they were made by now-vanished glaciers. And in the last 10 years, data from ground-penetrating radars and other orbiting detectors have told scientists that water ice lies under the surface across much of Mars.

How much ice? More than 5 million cubic kilometers (1.2 million cubic miles) of ice have been identified at or near the surface of today's Mars. Melted, this is enough to cover the whole planet to a depth of 35 meters (115 feet). Even more ice is likely to be locked away in the deep subsurface.

Most Martian ice lies underground because it cannot survive for long if exposed at the surface today. Sunlight's warmth and a thin atmosphere cause exposed ice to sublimate — pass directly from a solid state into a gas without melting. Only the poles remain cold enough to permit exposed water ice year-round.

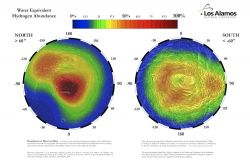

Where is subsurface ice on Mars now? The Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometers on NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter identified large amounts of hydrogen in the upper soil. Mars scientists use hydrogen as a stand-in for water because water contains two atoms of hydrogen and one of oxygen (H2O).

When mapped, the subsurface hydrogen data shows an interesting global pattern. At the poles, unsurprisingly, the concentration of water ice in the ground is essentially 100%. Poleward of 60° latitude (north and south), ice concentrations exceed 20% almost everywhere. In 2008 the Phoenix lander set down at 68° north, where it found solid water ice after scraping away a few inches of dry soil. The exposed ice sublimated away after a few days' exposure.

At latitudes below 60°, ground ice becomes patchy. The largest concentrations — roughly 10% — lie around the Elysium volcanoes, Terra Sabaea, and northwest of Terra Sirenum.

Detailed images of small impact craters by the HiRISE camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have extended the ground ice story. HiRISE has photographed a number of small impact craters made in the last several years.

Some show bright white "splashes" of ice inside the crater or scattered on the ground around it. The straightforward conclusion is that water ice lies at shallow depths closer to the equator than scientists previously thought.

If ice can't exist today at these latitudes, how did the ice get there? The answer, scientists think, is that it's a remnant of the last Martian ice age. Mars undergoes periodic changes in the tilt of its rotation axis with regard to the Sun.

When the tilt increases to values of 40° and more (currently it's 25° and it can go as high as 80°), the polar regions become warmer, and snow and ice accumulate near the equator.

Scientists have yet to map all the locations of subsurface ice. But researchers are becoming aware that water ice may exist at shallow depths in many places overlooked in the past.